Surviving the Holocaust: Robert F. Teitel’s Tale of Family

December 5, 2022

Consider the following three events.

1935. A brilliant and outspoken Jewish chess player and polyglot named A.M. Teitel is making a name for himself as a frequent speaker in the Wuppertal committee, an organization created to combat rising antisemitism and Nazism. His involvement in this group will place him on the watch list of the Nazi SS, and will eventually lead to his execution in a German prison camp in Malthusen that is unreported to his family until years later.

1944. A 3 year old Jewish boy lies hidden in plain sight on a farm in the Dutch countryside, kept out of sight by his mother from desperate Nazis as an Allied death knell ensnares the Third Reich. After the boy’s mother dies due to food blockades, leaving him an orphan, he will come to cross the Atlantic Ocean to the United States in a tiny metal bird unaccompanied and unable to speak a lick of English.

1947. In a case that would become national news, a Dutch newspaper reports the curious case of a man who has kidnapped his own grandchild, whisking him off under the proverbial cover of darkness through a war ravaged Europe. After stays in Belgium and Switzerland, the child finally returns to the orphanage amidst a flurry of press coverage. The child would later come to the US to stay with his grandfather, after another sublime bit of chutzpah would lead grandfather to testify on behalf of grandson in front of Franklin D. Roosevelt. The result would be the passing of a congressional act personally addressing the immigration status of one Robert F. Teitel.

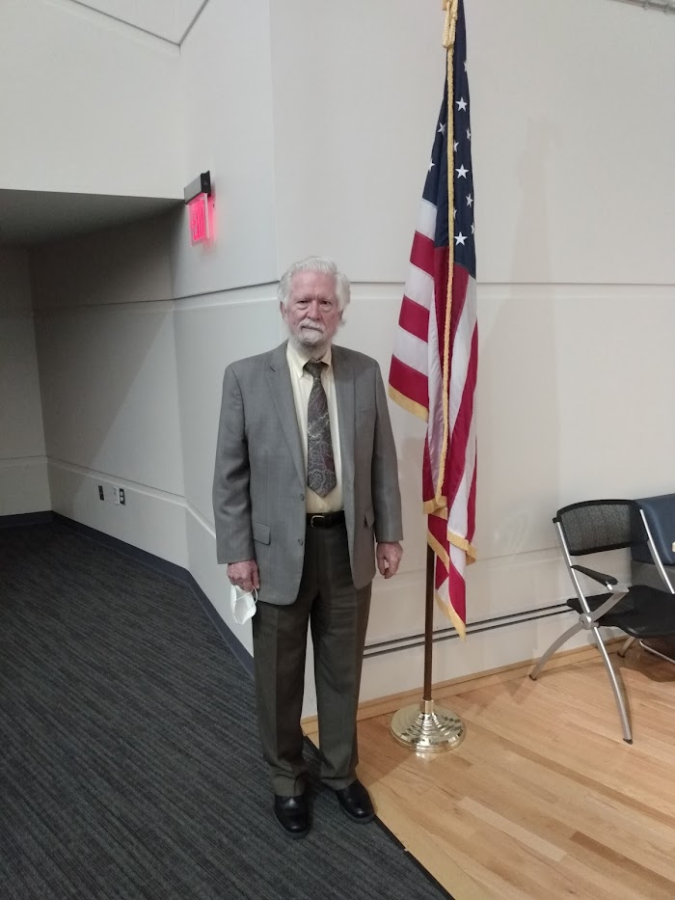

These events are not separate premises for upcoming Tarantino blockbusters, but are parts of the incredible life of Robert F. Teitel, a retired professor of statistics and a speaker through the Frank Islam Athenaeum Symposia Speaker Series two weeks ago on November 17th. Through meticulous collection of historical records, Teitel presented the narrative of his life to an audience of a hundred, filling the room with a story of chutzpah, surprising moments of levity, and resilient pride in his family despite their fateful entanglement in the events of the 20th century.

“Here is a news clipping from one of my father’s games in the local paper…he spoke Yiddish, Hebrew, English…a bit of Arabic…I wish I had that skill” narrates Teitel methodically, as he shows documents on the large slideshow screen. “On one fateful morning in 1937, A.M Teitel happened to leave his house at the same time my mother did. A year later, they were eloping to Jerusalem.” Moments of happiness like this, as in all true stories, punctuate the talk. They’re a reminder that despite the influence historical circumstance may play in determining the broader direction of our lives, lives in their subjectivity can never simply be defined as the events that shape them.

“In 1939 my father passes his engineering exam[…]and my parents move to Amsterdam as my father becomes an engineer at the Faulker airplane factory – which would later be taken over by Germany.” Thus continues Teitel, his story picking up in its psychological depth as history unfolds beneath it. “In 1942 my father, who had been under investigation by the Nazi Secret police (SS), is finally sent to Amesfoort prison in Grmany[…]He will be executed in Malthusen on the 19th of October 1942. They told my family that he was still alive…My mother believed that lie for years.”

Broader Efforts

Teitel’s presence is part of a wider project by the Paul Peck Humanities Institute (PPHI) to renew the remembrance of the events of the Holocaust and the stories of its survivors. The effort spans multiple projects including the Portraits of Life: Holocaust Survivor’s of Montgomery County project and a digital storytelling internship program in partnership with the Smithsonian Institute. Spearheaded by the late Dr. Myrna Goldberg in the 90’s the project of Holocaust education has since been taken up by Sarah Ducey, the director of the PPHI, and Professor Ken Jaffe, who teaches art history at the college and was mentored by Goldberg herself.

“It’s impossible to do what she did, she had so much energy” says Jaffe of Goldberg. “She’s the one who started it, and it’s been continuous since then.” It’s a special project, he adds. “You just realize when you learn about individuals like that, there’s wonderful things about their lives[…]like with Mr. Teitel’s research, we can learn so much about these people. This project means a tremendous amount to me.”

“It’s one thing to hear [statistics], but first hand experience of the stories is just a different thing entirely” Says Brandon Rodriguez, a student at the college and an intern with the Digital Storytellers program. In partnership with the Smithsonian Institute, interns with the program help compiled video footage of Holocaust survivors for the renowned institute’s archives. “It’s opened up my view of history. The videos are still black and white, but it’s like ‘this is [someone like] me.”

Evidence that these efforts are more relevant than ever can be found abundantly in today’s political climate. Notably, well known rapper Ye (formerly of Kanye West fame) recently came under fire for Antisemitic remarks during interviews using pervasive, harmful stereotypes of Jewish people. More broadly the US has seen an upsurge in antisemitic acts, with The Anti-Defamation League – an organization tracking anti-Semitic violence in the US- finding 2,717 acts of Anti-Semitic violence in 2021 alone. It’s the highest annual total since the organization began tracking violence in 1979.

The consequences of larger sociopolitical currents loom large in Teitel’s talk as well, with fascism, nationalism, and the rise of authoritarian rulers making their mark on his family. Although unspoken, warning looms behind the words that Teitel speaks. His is a story not only of a bright immigrant orphan from the bustling Dutch industrial city of Den Haag, who learned English by reading the New York Times, but also the implicit fact that without the buildup of extreme ideology and manufactured hatred that swept Europe, perhaps he would have never had to.