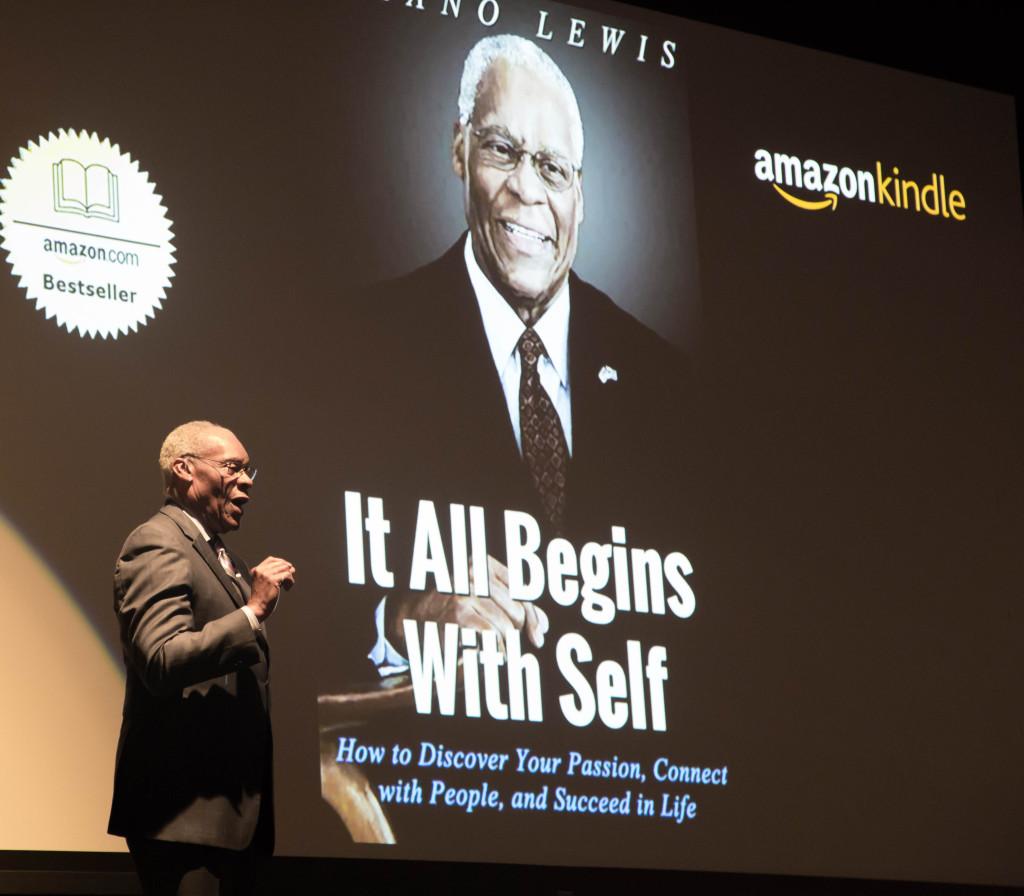

Race is a very daunting subject in the United States. Through the wide lens of history, the 150 years since the abolition of slavery is a short time. The descendants of those freed men and women had to face incredible hardships for over a century; there are people alive today who experienced first-hand segregation, bigotry, and discrimination during the Civil Rights era and earlier. One such person was Former Ambassador Delano Lewis. Having grown up in a segregated environment, to one day be the United States Ambassador to South Africa, he’s experienced, and overcome, and wishes to share his wisdom and thoughts on how we can approach race relations in our country and in our community. As he addresses the challenges of race in America, Lewis inspires hope while emphasizing a realistic and honest assessment of our environment.

Lewis grew up in Kansas and spent much of his childhood in a segregated community. His church, school, and neighborhood were all black. He shares this history to make an important point: that being exposed to racism has a powerful effect on a person’s psyche. Even as late as the age of 18, Lewis recounts an experience where, while in Seattle with a co-worker, he felt the need to ask at which place it would be acceptable for him, a person of color, to eat out. He was afraid of going into a wrong part of town and being hurt.

Lewis’s first experience meeting non-Black people was late in high school as part of an honor program’s mock student government. He candidly admits feelings of inner fear, of wondering if he could “measure up” in an integrated world. It was here that the belief in hard work instilled in him by his father allowed him to grow and find success. And he believes that everyone has the potential to flourish and succeed as he did.

Drawing on his experiences in youth and as an Ambassador, Lewis lays out that the key to progress is communication: dialogue, listening, respect, and understanding. But it also requires leadership. He illustrates this with the end of South African apartheid. Lewis says that in addition to the efforts of Nelson Mandela, the work of South African President F.W. de Klerk was also vital to the abolition of apartheid. While not all was perfect, Lewis says it took courage and initiative on de Klerk’s part to reach out to Mandela. De Klerk’s leadership, and willingness to communicate with and understand Mandela, paved the way for the civil rights changes that would soon take place. Lewis believes that there are leaders in America today that have the potential to show that same courage and initiative.

Lewis also expresses belief in the merits of the “Truth and Reconciliation Commission,” a system of restorative justice used in South Africa to allow victims of human rights violations to air their grievances at a public hearing and seek restitution and amnesty. While Lewis admits that there were flaws in its execution, he believes that it was important to let people know that the abuse and to expose the truth.

Non-violence and forgiveness are also central to Lewis’s ideals. He cites Mandela’s determination not to treat whites in the same way they treated blacks, and Mahatma Gandhi’s practice of passive resistance, but doesn’t shy away from the “resistance” aspect of that philosophy. While Lewis says that a person should not let racism be an excuse for not achieving success, he supplements that belief by saying that in order to rise above racism, a person has to confront it. They must know that it is there, resist labels and stereotypes, and actively speak out against it.

As Lewis concludes his speech, he leaves us with a light of optimism. As we’re approaching a historically divisive political era and general election, Lewis affirms his faith in the common people. That while progress might be slowed or expedited based on leadership, it will happen. If people will acknowledge racism’s existence and its effects, and co-operate to expose and confront it, we can overcome it and be a better nation. As a final call to action, Lewis proclaims, “Let’s do this together.”